Me in the middle, with Janet and Bill in 2021.

When my grandmother died in 1979, I drove my young wife and one-month old son from our home in Nashville, TN to the funeral in Wisconsin. Grandma was young enough to have a large funeral, just 72 years old. My age.

Of course, in Rio, WI, population 788, funerals were as big a social event as Friday night football at the field in Fireman’s Park. I didn’t play football. I ran cross country instead, which I convinced myself was harder.

But I was at the football games, either running the sideline keeping stats, or in the stands playing “CHARGE” on my trombone.

After grandma’s funeral service at Redeemer Lutheran, one of six churches in town – equal to the number of bars – everyone gathered in the church basement for a lunch prepared by women of the church. Because the meal was free, and there wasn’t much else happening in town that day, the room was crowded.

My wife was most concerned with the one-month old son not accustomed to the noise and crowd and whose only real concern was keeping his tummy full and his diaper dry. So, he started fussing and wailing and that’s not the sound you want to hear piercing the din of chattery family members chowing down on store bought dinner rolls filled with a slice of ham and a slab of butter, potato salad and red Jell-O with marshmallows.

Suddenly, from across the entire fellowship hall, packed hip to hip at the folding tables, my aunt Janet yelled, “Give that boy some titty!”

Now, in another context other than a rural Wisconsin farming community, that comment might have seemed out of place, even impolite. Certainly it caused all the blood in my wife’s body to flush to her toes and then recongregate in her face, making her flush a brighter red than the Rio High School Vikings mascot. But, it also gave her the freedom to excuse herself, find a quiet Sunday School classroom, and take care of our son’s immediate need.

Aunt Janet died this week, at age 91. She was my mother’s last surviving sibling and mom preceded her in death by 29 years. They were two of eight siblings, prompting my grandpa McFarlane to say he had “Two and a half-dozen children.” When grandma McFarlane died, petty sibling grievances broke familial bonds and later on, as one sibling after another died, obituaries did not list all surviving family members, as if they never existed.

But Aunt Janet was always a friend, in part due to the loquacious character of her husband, Bill, a former police officer and much longer a seed corn salesman who knew every farmer and what they needed most. Bill preceded her in death by three years.

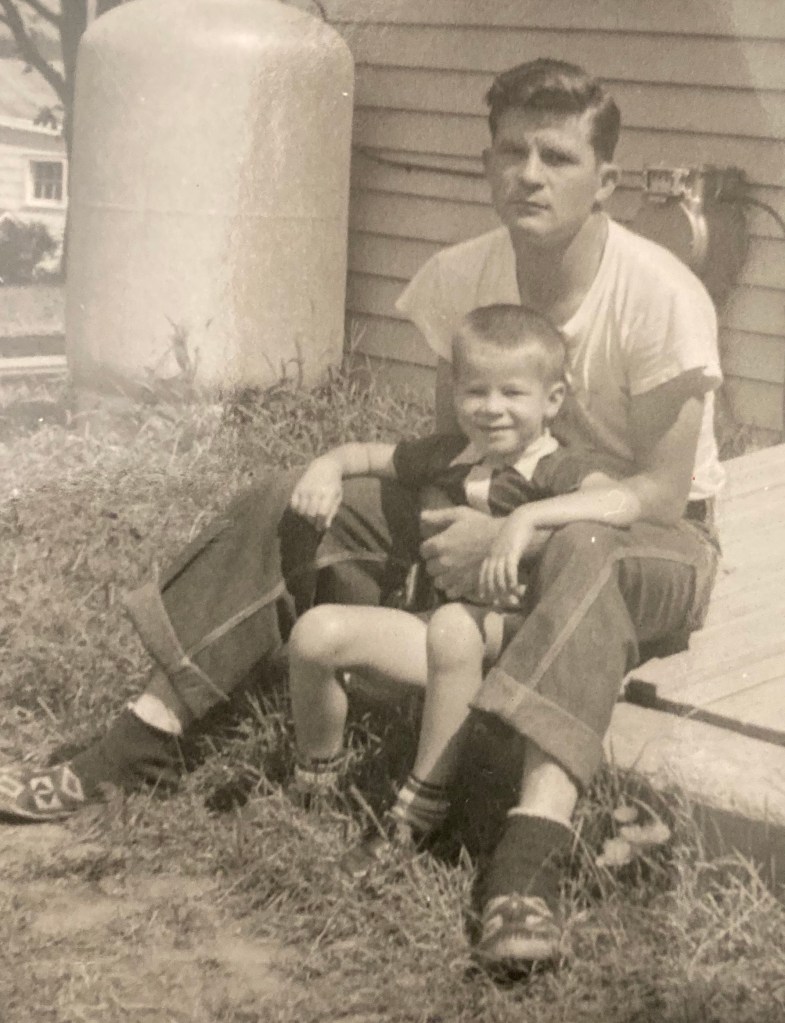

I confess Janet’s was the first bare breast I ever saw, as I stood wide-eyed at age five while she fed her first born son, Mark, a man who grew up to be a Presbyterian pastor, nurtured as he was on the milk of human kindness. He could preach from I Peter 2, “Like newborn babies, crave pure spiritual milk, so that by it you may grow up in your salvation.”

Janet and Bill had five children and 10 grandchildren and money never flowed like water over Niagara. Janet always put her hand to the wheel to find additional resources, driving school bus for more than two decades and making wedding cakes for lucky brides and grooms.

She looked at driving bus as ministry, taking the opportunity to offer a bright, encouraging word to children with dour faces, lifting heavy, reluctant feet up the step on the way to school.

She was certain of opinion and ready with advice.

When Janet learned my cousin Allen smoked, she asked if he would rather kiss a girl or an ashtray. Allen, sarcastically defending his nasty habit, told me he responded “Ashtray.” He’s since grown beyond that – both in girls and habit.

Janet and Bill built a house on a hill overlooking that of her mother Eva and she was diligent in looking after her mother to the end. Eva –my grandmother on my mother’s side – expressed concern that bad weather would limit the size of her funeral. She was mentally comparing her eventual celebration to the big crowd that showed up for her husband’s sendoff. In her mind, her funeral would suffer by comparison and somehow that would reflect negatively on her life.

Though such comparison is a false equivalency, if every person whose life Janet affected positively were to attend her funeral, ushers will need to bring in extra chairs.