While riding the bike lane on Longboat Key in Florida, a large SUV glided up beside me and slowed, matching my speed. Given the culture of animosity between cyclists and automobile drivers who think the road was laid for them personally and that any other user traveling five miles per hour slower than them is an impediment expressly forbidden in the Constitution, I kept my eye on it.

I’ve had doors opened to try to knock me off my bike, soda cans tossed at me and curses cast on the wind as cars pass that I can barely hear and never understand except for their volume and intent. I always laugh when people fly by me, shouting some insult that never registers because those idiots don’t realize their words dissipate in the wind like bubbles touching grass blades.

And there are the truck guys immobilized in lines of traffic driving onto the island who see me about to pass unimpeded in the bike lane so they turn their wheels and edge into my space, laughing all the way. I have the last laugh as I rap their truck with my knuckles and roll on, their being impotent – despite their big truck and heavy belt buckle – to bother me at all.

So, this creeping SUV concerns me until I notice its right directional signal blinking. He’s waiting for me to safely pass through the intersection before he turns right, behind me instead of in front of me, avoiding a collision.

May his tribe increase.

The summer of 1972 I took off on my bike from south central Wisconsin to ride 300 miles to Wayzata, MN to see a girl I’d grown close to during my one year at Luther College. I took off on my 10-speed Schwinn wearing cutoff shorts and tennis shoes. I carried a few cans of tuna fish, a few bucks, a water bottle and a sleeping bag.

I had no rain gear, no shelter, no tire repair kit, no helmet, no sunglasses. I’d bought the bike for ten bucks from a friend who’d left it outside all winter in the Iowa snow. And my route on Highway 16 was a major thoroughfare.

I rode 75 miles the first day, at least three times longer than any single ride I’d done before. I slept on the ground in some city park, uninterrupted except for the bug that crawled into my ear. It navigated deeper than I could reach with my finger and in my sleepy desperation I used the plastic tip of my shoe string to squish it so I could get back to sleep.

When I slung my leg over the saddle the next morning for the second leg of my trip, I was so tender I felt like I sat on the sharp edge of a sword.

During that trip, a car passed me just like the SUV on Longboat Key, but he turned right directly in front of me and I crashed into its side. I hit the pavement and the car stopped long enough for the driver to see that I was uninjured before it sped off.

That was on my mind as I watched the SUV beside me.

I’ve ridden across Wisconsin and North Carolina. I’ve ridden RAGBRAI across Iowa four times. My bike travels with me so I’ve ridden in many states and I’m always cognizant of the risk I’m at from inattentive drivers.

In 2023, 1,166 bicyclists were killed in crashes with motor vehicles, an 86 percent increase from 2010. Approximately 130,000 cyclists are injured annually on U.S. roads.

The common excuse of deadly drivers is “I didn’t see him.” That is NEVER an excuse. A driver is responsible to see everything in his path, from a pothole, to a stop sign, to a kid running into the street to chase a ball, to a cyclist in brightly colored clothes likely adorned with flashing lights.

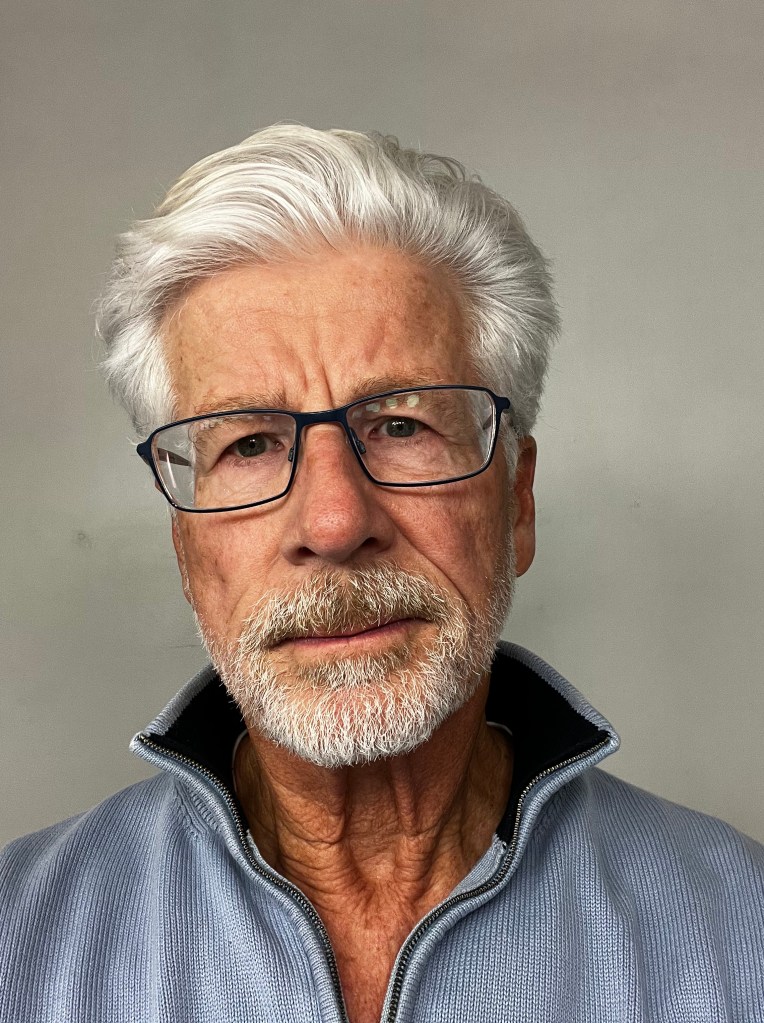

I’m a little more nervous on the road now, at age 73, more aware of how close cars, trucks and landscaper trailers are to me when they pass; more aware of how distracted and careless drivers are generally.

And more appreciative of the rare auto driver who gives me a wide berth and slows to turn behind me, rather than in front.