In a service economy, how do you find those who will serve?

Remember when the misguided guidance during Covid 19 lockdowns declared that only “essential” workers could go into their jobs? Those declared “essential” weren’t the pencil pushers. Not the multiple degreed, private office, soft hands, computer monitoring, expense account, long lunches crowd. It was the people who really keep society running: the grocers, plumbers, gas pumpers, street maintenance, garbage collectors, furnace fixers and liquor store clerks.

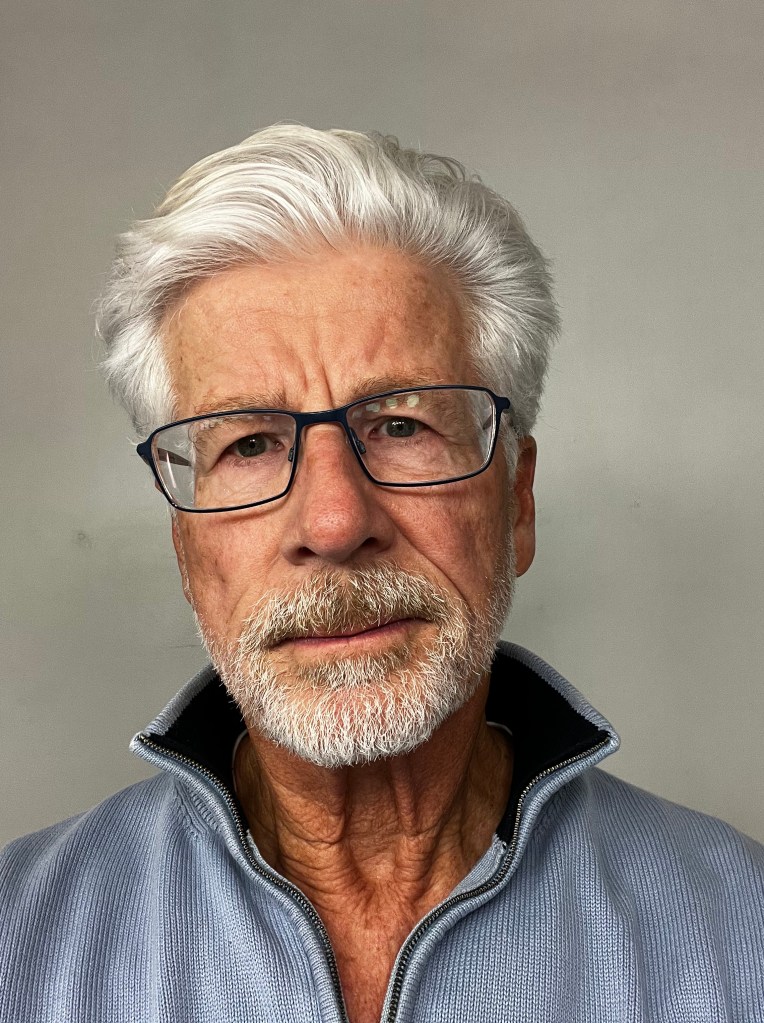

When my youngest grandson was six he declined to help me shovel wood chips into the tractor bucket, despite the fact that I’d provided him an appropriately sized shovel. Sensing an obvious teaching moment, I paused to deliver an insightful life lesson.

“Corbin,” I said. “In this world nothing gets done without someone doing it, someone actually putting his shoulder to the task, picking up a shovel, swinging a hammer or carrying the load. Some people just want to talk about the job. Others actually do the job.”

With confident aplomb, Corbin said, “Papa, you’re a doer. I’m a talker.”

Growing up in a farming community in southern Wisconsin, I didn’t know many talkers. We were doers or we were not eaters.

Mine was a small town, a tiny town really, 788 people. All the farmers knew which boys were aging up to be useful during summer hay baling, stone picking and corn detasseling seasons. Prime years were age 13 to 15 – 12 if their mama was hefty – strong enough to throw bales, but too young to work for the canning factory. We were ripe and easily enticed by the dollar an hour standard wage.

My uncle Donnie, the quintessential Norwegian Bachelor Farmer, trained me in most things “farm.” I lived on one side of town, in the country. He lived clear on the other side of town, in the country. We were three miles apart.

I still check the weather frequently, a farm life habit when unreliable forecasts influenced our decisions to cut the alfalfa today, or tomorrow. Will we have three days of sun after we cut it? If it’s going to rain before it’s dried enough to bale, we’ll lose most of the leaves and nutritional value as cow feed.

Now, I check the weather because I want to know if it’s going to be warm enough for a bike ride, dry enough for pickleball or sunny enough for a beach day.

Us hay haulers and stone pickers typically had a main farmer we worked for, someone who would call us first when he needed a hand, someone who asked if we’d be available in three days.

But not everyone cut hay on the same day, so we were glad when the phone rang with work for others. In addition to my uncle Donnie, I liked to work for Bob Manweller or Donovan Selle because they paid $1.25 an hour. Mrs. Selle put on a mean feed, too, and her pretty daughter managed to make herself discreetly visible.

I’ve been a doer my whole life – my wife would say people pleaser – and I swelled with pride when my dad bragged about my work ethic to friends: the way I split wood to feed the basement furnace, or cleaned the stable or mowed the yard. More than the doing, seeing what was done is the source of deep satisfaction for me.

Last year we had to reshingle our roof and put in a new furnace. I couldn’t do either one of those tasks. I did reshingle our first house in 1977, a house so small that when I put in the order, the salesman asked if I was going to cover only part of the house.

But this roofline is much more complicated. And furnaces are huge jobs, and who can fathom the pipes under the kitchen sink and where does the contents of my garbage can go on Thursdays and how does someone in Charlotte restart my modem in Winston-Salem, and when my car tires want to meander how does a guy realign them?

An average of one college a week closes its doors in this country, partly because demographics reveal fewer 18-year-olds, and partly because young people are re-evaluating the benefits of college, realizing that doers can start a career much sooner than talkers and four years later, have no student debt.

Here’s to the doers in the economy. May their tribe increase.