I turned old on August 30, 2025. I know the day. And the hour. And the moment.

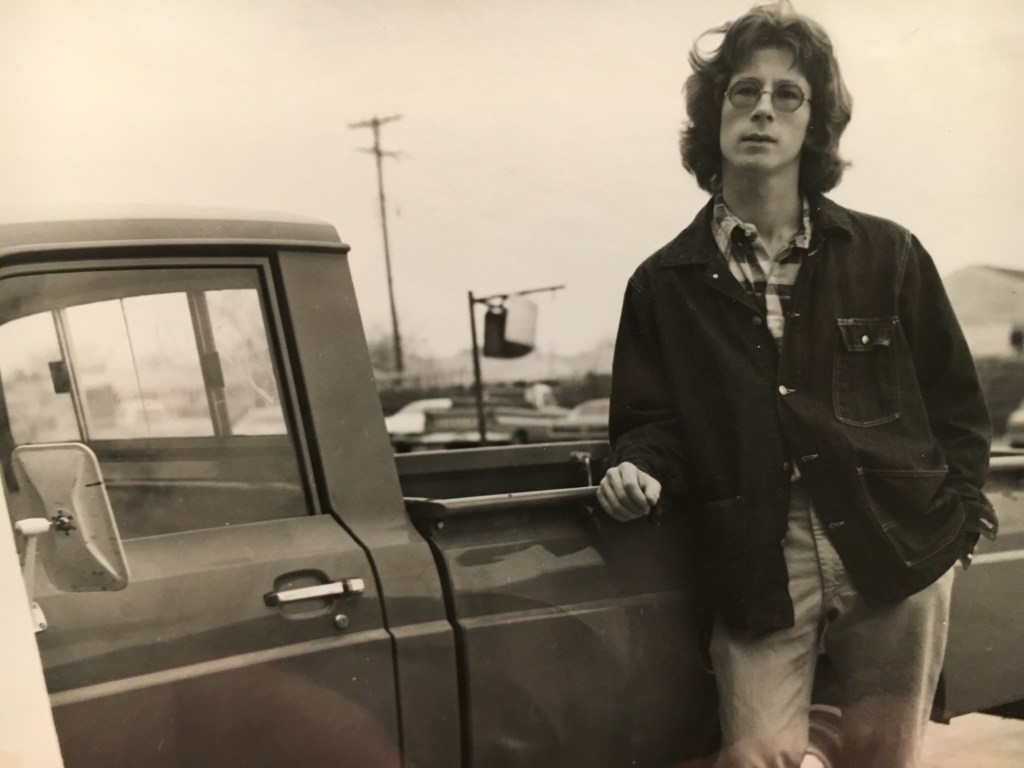

For much of my life, I looked younger than my age. I was a husband, father, and owned my second house before I shaved every day.

About age 26, I was in the barber chair with my hair wet and glasses off and my wife walked in, ready to take me home when I was finished, since we managed with one car. The barber noticed that she caught my eye, and asked, “Is that your mother?”

Later we listed some furniture for sale, some of our original “we-need-something-and-this-will-do-until-we-have-money,” pieces. A college girl called, said it would be perfect for her dorm, and arranged a time to come pick it up.

When I answered the door, she looked at me and asked, “Is your mother home?”

To say I was devastated is to say the Johnstown Flood was a trickle. I was floored. It took me days to get over it. Evidently, I still haven’t.

I was a college graduate, Army veteran, working a professional job with national connections and a college girl sees me in my Saturday morning T-shirt and jeans and asks if my mother is home.

I told her my mother lives in Wisconsin, 640 miles away, but if she’s here for the furniture, I can help. And then my wife picked me up off the floor.

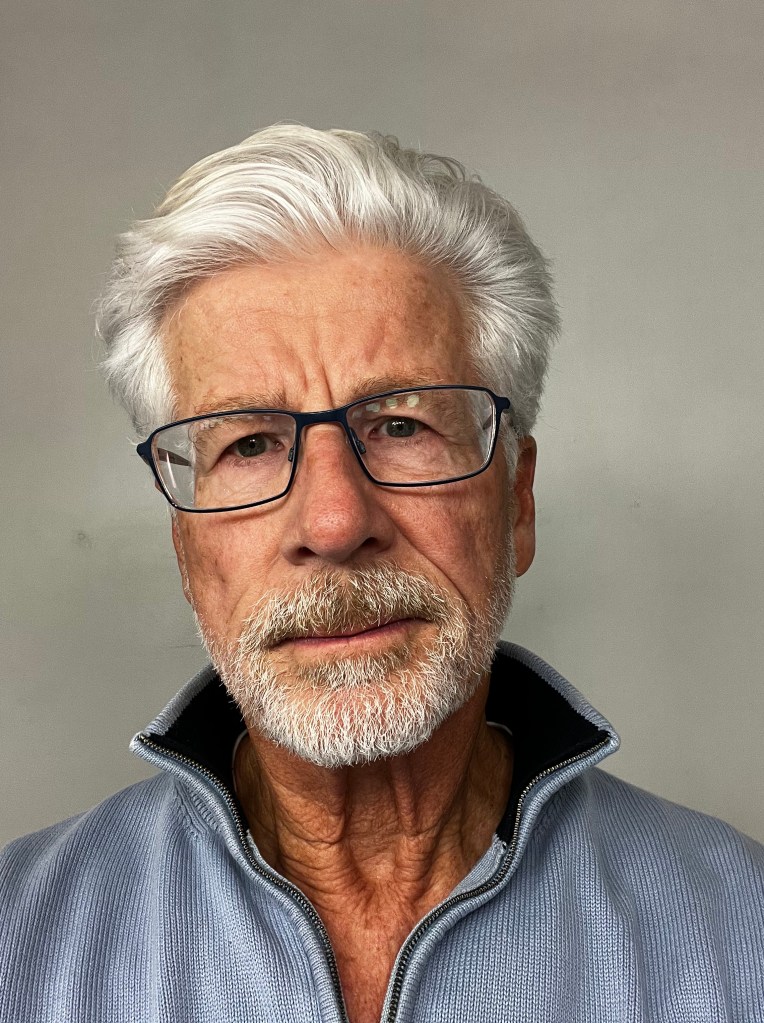

Eventually, the sirocco winds of life aged my face, bleached my hair to arctic blonde and added enough wrinkles that I didn’t have to say, “No, really” anymore when my age came up.

My oldest son shares some of my facial features and when I’m introduced as his father, his friends invariably say, “I could’ve guessed.” I keep hoping one day someone will mistake me for his older brother.

Which brings me to the fateful day when the harsh reality of simple observation by a stranger shattered the mistaken impression that all the mirrors in my house are broken. I walk past a mirror, see the image it reflects, and I know that grizzled face can’t be me.

And yet.

In Budapest, Hungary at the beginning of a Danube River cruise taken to celebrate the 50th anniversary of marriage to a beautiful woman I had bamboozled long enough to convince her to marry me, the curtain came down on my illusion.

I stepped onto a tram car and a young woman stood to offer me her seat.

Glass shattered. Ego crumbled. Humility fallen over my shoulders like a granite yoke.

I implored the innocent to return to her seat. Over a language barrier, my pleading eyes, exasperated face and arm motions made my intention clear. “Please. No. Take your seat. ARRGGG.”

She politely declined, and I resolutely remained standing, amid the laughter of our traveling colleagues.

The insult of reality was exacerbated the next day when on a similar tram, my wife was warned that a conductor was on board and was checking tickets. In Budapest persons over age 65 ride public transportation free. The local was kindly warning my wife that she needed a ticket.

Sue Ellen graciously informed her that she didn’t need a ticket, because she was 70. To which the kind commuter expressed astonishment, of course.

She then looked at me, seeing I was with Sue Ellen, and I swear I heard her ask, “Is that your father?”

‘/